Those ideas would see the light of day on the OJay's 1976 song Rich Get Richer taken from their gold-selling Message In The Music album:

"There's only sixteen families that control the whole world, I read that in a book ya’ll ; People like the Mellons, the Gettys, the DuPonts, the Rockerfellers, Howard Hughes, if they always win, how in the world can they lose"

Leaving no topical stone unturned, Gamble penned chilling first-hand narratives that dealt with everything from slavery (Ship Ahoy), the prison industrial-complex (I'm Just A Prisoner), and superficial Black unity ("Don't Call Me Brother"). Songs like Family Reunion were aural ancestral family heirlooms. Gamble challenged America's penchant for war (" Man of War") and explored religious conflict ("War of the Gods"). He even challenged the urban policies of Philadelphia's polarizing mayor Frank Rizzo (''Let's Clean Up The Ghetto.").

Non-Gamble compositions were given progressive makeovers. Before sampling, Malcolm X and MLK speeches were spliced onto a remake of Paul McCartney's 1976 Let'Em In.

On the back of Philly International album covers Gamble dropped jewels influenced by

his Islamic leanings. He spoke of "universal truth" and urged listeners

to strive and grow into their "god-like condition. " As Gamble pondered what good was "wisdom" without understanding," he warned of the coming of a "divine vanguard"---an "army of truth

and justice for all humanity."

On the O'Jays' Family Reunion (1975) album, Gamble condemned the generational gap as a "divisive evil plan to halt the wisdom between

young and old as well as stifling the energy of youth which is the

stabilizer of wisdom and age."

One of Gamble's most powerful statements was on Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes 1975 album Wake Up Everybody:

''The kingdom of God is here on earth today! The righteous government we prayed for so long. Thy kingdom come, thy will be done on earth. Open your heart so your mind so your body can feel it. Open up your eyes to so your mind can feel it. The paradise lost is the paradise regained. Wake up everybody!!! "

Gamble occasionally filtered his strident messages through the female voices. The Three Degrees' Year of Decision ("this is the year to get what you need/there is no reason why/you you should be shy/ people died to set you free") and The Jones Girls' At Peace With Woman ("there won't be peace on this ground/til man and woman sit down") were a few examples.

Primarily speaking through the overt masculinity of the power trio of Billy Paul, Theodore Pendergrass, and Eddie Levert, Gamble transformed them into urban griots detailing 360

degrees of the human condition. Paul's

moody blues, Pendergrass' gospel bark, and Levert's chesty bluster (and partner Walter William's aching despair) were a perfect foil for protest songs (Give The People What They Want), hard-luck tales (Survival, Let The Dollar Circulate) and sharp indictments targeting blatant materialism (For The Love of Money),

Exploring the world of unscrupulous people and shallow social climbers (Shifty, Shady, Jealous Kind of People and Be For Real), Gamble's real-life stories were as potent as pages torn from a Shakespearean Greek tragedy.

Critics accused Gamble of using his acts to further his political agenda. Panning the subject matter, they dismissed it as heavy-handed. Music critic Robert Christgau cast Gamble as "self-serving and "psuedo-political" and a "gifted pop demagogue/black capitalist posing as a liberator." Branding the OJays' 1975 Family Reunion album as "Jesse Jackson (or Reverend Ike ) goes disco," Gamble's patriarchal-slanted creativity---foreshadowing Spike Lee and Chuck D's similarly maligned output later on---was heavily criticized. Christgau lampooned Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes' Wake Up Everybody for its "muddled-headed lyrics of war, hatred, and poverty that came along just as Gamble and Huff were running out of lyrics."

As rock and folk genres were free to explore social commentary, Black music was grounded and confined to the spit-and-polish of an industry tried-and-true conceptual formula.

Songs like Change Is Gonna Come (1964), Respect (1967), and Sitting On The Dock of the Bay (1967)---with their "coded" lyrics push the needle closer to center.

Black rock collective The Chambers Brothers---a blueprint from everyone from the Isley Brothers to Bad Brains to Living Color---delivered definitive anthem Time Has Come Today (1967) departing from the projection of non-confrontational images of Black entertainers to the American public. As the 70s dawned, Philadelphia International continued on the path laid out by its predecessors.

Gamble's

penchant for message for music wasn't just an artistic concession to a

fertile period. Spirituality, consciousness, and civic-mindedness were

always in his DNA. Born

the son of a devout Jehovah's Witness, during lean times a young Gamble and

his family feasted at sumptuous banquets sponsored by Father Divine---the

self-proclaimed god-in- person and leader of the Peace Mission, a

predominately Black commune preaching self-sufficiency, racial harmony, and civil rights.

Like

Marcus Garvey and Elijah Muhammad, Father Divine created a cooperative

blueprint providing jobs, education, and housing for his congregation

while feeding thousands of poor people during the Great Depression. The

seminal spiritual leader would greet followers with a phrase destined to

live on in Black vernacular, hip hop, and pop culture circles: peace.

The

Nation of Islam's strong Philadelphia presence coupled with the Leon

Sullivan and Cecil B. Moore's community activism were sources of

inspiration and fueled Gamble's own spiritual, and community-based

endeavors and of course----his song lyrics:

"God is just a title; It's like calling.somebody/father/preacher/presidential/general

Allah/Buddah/Hare Krishna/Jehovah/just to mention a few; some people even call Jesus God too

Love peace and eternal life is your reward

to anyone who knocks on your door

There's only one god is true/and all the names are not the same/one day the people of the world will know your great name/ you are at the strong/you are the mighty

I hope I'm with you when they start to fighting/ love, peace & eternal life is what I want:”

---War of The Gods (1973)

Heavenly father/creator of all things/I humble myself as I bow to your throne/ I pray for love/ joy/peace and happiness to present in my home/and let your holy spirit dwell in my heart in my mind:” ----A Prayer (1976)

"Get in line/start marching in time/you better make up your mind/we're gonna leave you behind"

----Am I Black Enough For You (1973)

"If you read in Proverbs 25:13

You'd see where it says:

As the cold of snow in the time of harvest

so is a faithful messenger to them that send him:

For he refresheth the soul of his masters

He said get on up, get on up

Get on up, go out and tell the world"

---Somebody Told Me (1977)

"How can you call me brother/when you ain't searchin' for the truth?"

----Don't Call Me Brother (1973)

"They played a game of divide of conquer/since the world began/ tried their best/to separate the people/so we couldn't understand"

----Unity (1975)

In time, there would be internal pushback. After recording five consecutive gold/platinum albums of socially-conscious music material between 1972-1977. The O'Jays were looking to leave the message songs behind. They would get their wish with 1978's million-seller So Full of Love featuring hits like Use To Be My Girl, Brandy, and Cry Together. In the years to come their concert setlists would exclude the bulk of their message material.

In 1972, journeyman singer Billy Paul stood on the cusp of superstardom with Me and Mrs. Jones. When his follow-up and Gamble-penned Am I Black Enough For You hit the airwaves, it alienated audiences. Paul never returned to pop success again and blamed Gamble for fumbling his career momentum. Over the years both would have differing accounts of the release that rested between being "artistically honest and commercially misguided."

Philly International compositions Love Train, Me and Mrs. Jones, When Will I See You Again, and If You Don't Know Me By Now are highly clebrated in pop circles. Ballads You Got Your Hooks in Me, Sunshine and I Hope We'll Be Together Soon are beloved by hardcore fans. Beyond major hits and fan favorites, PIR's creative ambition tends to get lost in the shuffle.

The

depth of the label's albums gave record buyers a total listening

experience. O'Jays and Blue Notes albums regularly sold gold or

platinum, shattering the industry glass ceiling mentality that only

singles drove Black record sales.

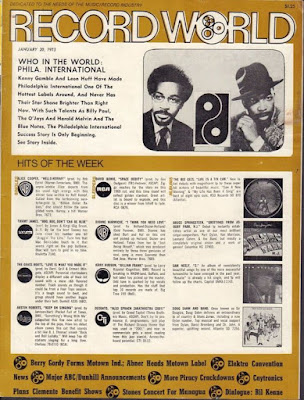

According to LeBaron Taylor---"godfather" of Black crossover strategy and vice-president of CBS Records' special markets servicing Gamble and Huff material---by 1979, his division accounted for 40 per cent of the CBS roster, 25 percent of the label's roster and $97 million dollars in revenue. An early catalyst to this success was Gamble and Huff's output.

One year of signing with CBS, Philly International would sell over 10 million records. I can't tell how many households I encountered as a kid that had Family Reunion and Wake Up Everybody in their album collections.

Back in the late 80s---during Motown's resurgence as a legacy label, GQ Magazine featured an article by esteemed Rolling Stone music journalist Ben Fong-Torres questioning Philly International's ability to ascend to Motown's iconic status. PIR's artists were dismissed as "journeyman" acts (compared to Motown's galaxy of stars ) whose careers were revived by the Philly Soul Machine.

As Motown basked in the glory of having their catalog reissued, reinterpreted, and appearing in films---Fong-Torres rendered the Philadelphia International catalog as unsuitable for box set reissue (there's four and counting). Thank god he was wrong.

The

legacy of Gamble (and his comrades) survives today having to weather the storm of disgruntled attitudes and less-than-favorable comments

regarding PIR business and compensation practices during the label's glory

days.

Over the years Black music ended up in a strange place. In the 80s, R&B's champagne-and-roses aesthetic was considered a step behind hip hop's creative urgency. In the late 90s and early 2000s, both genres were split down the middle: female R&B fans on one side and male rap devotees on the other. Disputes over the definition of rap "lyricism" and "conscious artists" linger today. Aside from a select few, an artist's protest platform remains separate from their creative content.

I can remember a time when such divergents were nonexistent. When Black music could be inspirational and aspirational. When it revolved around its own orbit and its fan base was worth its weight in platinum and gold. The artistic gifts of the few were enjoyed from a distance by the many. Together both were in lockstep---bound by songs in the key life that celebrated the life of the everyman. Audiences were transfixed and rejuvenated by the message in the music. They responded to the call to understand while they danced.

Kenny Gamble's lyrical genius displayed a keen observation that was sharp as a blade. His visionary master plan was as lofty as clouds in the sky. His gifts are forever immortal.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-550002-1474575567-4884.jpeg.jpg)

Outstanding Read! Kenny Gamble is really somebody special. You did a great job of describing this Giant and still it's still more to say about the Mighty 3. Look forward to hear more.

ReplyDeleteThank you for reading

DeleteI have some other pieces about Philly International as well.

DeleteI can forward them to you

Delete