Keys To The City: Unraveling The Legacy of Mayor Richard Gordon Hatcher

From protest to politics. Unsung civil rights leader Bayard Rustin's depiction of transitional Black mobilization is resurrected by the Reverend Al Sharpton in Maynard--- the Netflix documentary of Maynard Jackson, Atlanta's first African-American mayor. Sharpton connected the dots leading to Jackson's seminal moment during Maynard's opening scenes: "In '65 when the Voting Rights Act passed and I think that in '68 when Dr. King was killed, it gave a new energy that we wanted political power and we exercised our right to vote."

Jackson's 1972 political ascent came on the heels of Richard Gordon Hatcher, one of first two Black mayors elected to an American city five years earlier. Navigating Gary, Indiana through optimistic and turbulent times, supporters honor his legacy. Skeptics are hesitant to give praise. Hatcher's appointment represents an ancestral deja vu moment. Lodged between past and present, it has deep and significant historical connotations.

ACT I: DREAMED FULFILLED

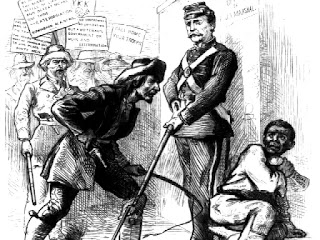

On November 16,1867, Harper's Weekly Magazine published an image entitled The First Vote. Depicting African Americans casting their votes during post-slavery/Civil War Reconstruction, the picture represented a seminal era of Black political activity that saw mass voter turn out. 90,000 Negroes voted in Virginia alone. Others would assume positions in Congress for the first time.

Black political progress was short lived. Democratic presidential hopeful Rutherford B. Hayes was caught at a political crossroads: defend newly acquired Negro citizenship or become an advocate of what whitehouse.gov described as southern "wise, honest, and peaceful self-government." Leaning toward southern self-government in exchange for Republican electoral votes to secured his victory, it prompted a return to a system thrusting Negroes back to a social climate that was akin to slavery.

One hundred years later, souls of Negro disenfranchised voters could finally rest. Hatcher won the election by 18,000 votes. Ebony ("Black

Power at the Polls") told stories of how Hatcher's navigation of political roadblocks on the way to victory---he beat a strong Republican opponent. Overturning voting lists fraudulently stacked against him and battling smear campaigns branding him a communist and racial extremist the new mayor-elect overcame it all. When Democratic organizers refused to provide financial assistance even though Hatcher was on the same ticket, campaign funds trickled in from as far as

Japan.

The Reading Article reported that the US Justice Department were backing Hatcher's claims that Gary's Republican machine were stifling Black votes. Ebony Magazine reported that a three-judge federal court investigation found that monetary rewards were offered to tear down Hatcher campaign signs. Names of nearly 5,000 African-American voters were removed from registration rolls and replaced with white votes. On election eve, 11000 fictitious names were found on voter registration lists located in white neighborhoods. Another twenty-five voters were discovered to be falsely registered to a 52-unit apartment building.

Polish-American resident Marian Tokarski revealed that she'd been duped into believing false claims that Hatcher was a communist. Exposing a vote-rigging plan involving city iron workers and prostitutes hired to cast votes in a white precinct under false names, Tokarski received anonymous death threats ("You will never live to shake his hand!") for coming forward.

Standing at the cusp of history, Gary, Indiana was on America's radar in '67. Fearful that African-Americans would desert the party if Hatcher lost the election, the National Democratic Party anxiously waited the outcome. Acknowledging the possibility of defeat, the clean-cut Hatcher proclaimed, "if I lose the election, I'll let my hair grow long. Singer Harry Belafonte and presidential-hopeful Robert F. Kennedy pledged support. Anticipating potential outbreak, the National Guard were dispatched to Gary streets to maintain order---similar to federal troops ordered to south during Reconstruction for similar reasons. In the end, all was quiet.

.

On November 7, 1967, all the votes had been tallied. Hatcher and Cleveland's Carl Stokes were hailed as architects of "the New Reconstruction & orchestrators of a "new era of Black politics."

The enlightened voters of Cleveland and Gary are a reflection of the spreading of the-I-can-see-the-light-philosophy that judges a man as an individual, not by a so-called race or religion or by the shape of his nose.

the Honorable Carl Stokes and Richard Hatcher are not black mayors, mind you: but these

distinguished mayors who happened to be born black.

Jesus, what a hallelujah time for America

A day of jubilee. Beat the drums. Sound the trumpets. Shoot the cannons.

Two soul brothers are in control.

--The Washington Afro-American (1967)

ACT II: TRUTH TO POWER

Men who are earnest are not afraid of consequences.

----Marcus Garvey

Well-regarded by his peers, Hatcher described by Ebony as the "dean of Black politics." When interviewed for a Hatcher piece in People Magazine, Detroit mayor Coleman Young sang his praises: "Gary probably reflects most of the problems of the urban cities and Dick has been able to handle them all." In addition to holding down mayoral duties, Hatcher held simultaneous posts as chairman of the Conference of

Black Mayors, vice president of the Democratic Committee and the international

chairman of the board of Trans Africa.

Operating with wide-ranging autonomy, Hatcher was a mayor who acted like a diplomat, giving new meaning to the term public servant. When the Democratic Committee allocated less than three

percent of a $30 million budget to Black businesses competing for

service contracts during a political convention, he headed to California to

balance the scales. A single day's activity included handling mayoral duties in Gary before heading to San Francisco

to meet with party officials and then on to DC for meeting with the US secretary of state.

| |||

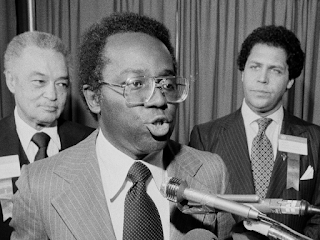

| Hatcher flanked by Detroit mayor Coleman Young and Atlanta mayor Maynard Jackson. |

Sitting for an Ebony interview ("Dean of Black Politics') in 1984, Hatcher ran down his hectic schedule: "I had a lot of things here to do in Gary but I had to fly to Washington for that meeting. We talked about the US invasion in Grenada, American policy in the Caribbean and the Middle East. We also discussed the fact that the State Department is one of the most segregated organizations in the United States."

Hatcher 's keen legal, government and business sense helped him to secure 30 million dollars for federal and private institutional municipal funding---fiscal procurements exceeding initiatives of all Gary's previous mayors combined. Brokering another 12 million from the Department of Housing and Urban Development, Hatcher eased poor housing conditions for neglected Blacks and senior citizens building 1200 low-to middle class housing units.

Acquiring

Department of Labor funding for job training and community self-help

programs, one project involved the refurbishment of a movie theater as

part of a proposed employment pathway toward construction vocations.

"Politically the Negro was even more exploitable. In the South, he couldn't vote. In Chicago he couldn't vote for the Democrat of choice. The Machine's precinct captains would go right into the voting booth with him to make sure he voted correctly. The major weapon was the threat. Negroes were warned that they would lose their welfare check, their public housing and their menial job if they didn't vote Democratic."

----(an excerpt taken from Mike Royko's Boss)

Down

south, state laws and mob rule controlled Black politics. Up north, Negro voters were at the mercy of powerful political machines like the one controlled by Richard Daley, Chicago's pugnacious five-term mayor. Part

Boss Tweed/part Bull Connor, Daley was lovingly referred to his white ethnic

constituents as "Hizzoner." Proclaiming himself the champion of the working man, he ran Chicago like a heavy-handy segregationist, inspiring journalist Mike Royko to pen a biography written in real time, detailing Daley's manipulative political activities.

As white flight emptied out Chicago's South Side, office holders/ward bosses remained in control over their old districts, parceling out employment opportunities, political favors and public assistance to incoming Southern Black migrants in return for votes. Boss tells the story of a young Jesse Jackson arriving on Daley's mayoral doorstep with a letter from a North Carolina governor endorsing him as a rising political prospect. In exchange for "rustling up" Black votes, Jackson was offered a job---as a highway toll collector.

70s sitcom Good Times---taking place in the Daley era, features fictional character Alderman Fred Davis a symbol of exploitative Black politicians also part of the Daley machine.

Hatcher would encountered similar experiences in Gary politics. Fresh out of law school and brimming with "idealism, ambition and hope" he discovered that the Democratic machine had things "locked up"("You couldn't run for office without its blessing"). Pushing back against unbalanced political relationships and barter systems, The Dispatch reported

that Hatcher and his political contemporaries had formed an alliance to

institute a Black candidacy protest to "keep the Democratic Party for

taking us for granted." Labeled in the press as a "Black political family." Hatcher and his team laid out a political agenda to select their own African-American presidential candidate but during the vetting process, Jesse Jackson broke ranks to enter the '84 presidential race. Hatcher served as campaign national chairman.

There was a time when Jackson's bet was on his friend. In 1978, Hatcher reluctantly passed on Jimmy Carter's offer to join his presidential cabinet as a special advisor on urban affairs. Jackson considered Carter's offer superficial and reeking of tokenism. In an interview with People Magazine, he bluntly offered his opinion: "There's no one on the president's staff with the credentials

for him to have Hatcher answer to him---he's presidential himself."

For wife Ruthellyn, becoming the wife of a DC politician was not in her future: "I hate to see my husband limited to Gary, but I'm a homebody and not comfortable in politics." Leaving small town Gary for a key cabinet position would have placed Hatcher on the political fast track, planting seeds for a possible presidential run in '84 or '88. Refusing to abandon the city, he made no hesitation where his loyalties lay: "the last ten years the people of

Gary shared my dreams. My job is to improve their quality of life." In the end, it would be Jesse Jackson's political audacity that was destined forerunner to Obama's run.

Hatcher's sharp intelligence and political astuteness were similar attributes later seen in the future president. His eye glasses and buttoned-up appearance made him appear more like a college professor (which he'd become later) instead of the leader of one of America's toughest cities. His demeanor contrasted with Jackson's flashy charisma and brash colleague/Detroit mayor Coleman Young's profanity-laced tirades against adversaries. He was no less fearless.

Others were content with having a seat at the table to express their concerns. Hatcher boldly challenged the status quo. Accusing President Ronald Reagan of "washing his

hands" of the "poor, Black, Latin and the elderly" Hatcher opposed the transfer delivery of federal domestic programs back to state authority outlined in Reagan's "new federalism" program, arguing that state neglect was the reason why these federal programs were created in the first place.

Writer Jeffrey Adler's book African-American Mayors: Race, Politics and the American City details how Hatcher's criticism of Reagan's policies angered First Lady Nancy Reagan. Ever protective of her husband, she demanded Hatcher be banned from the White House.

Criticisms weren't just reserved for conservatives. Hatcher called out the

Democratic Party for suffering an "identity crisis for aspiring to become a

"second Republican party" due to its "condescending

liberalism." Before Jackson's Rainbow Coalition, Hatcher advocated for political and social alliance between radical whites,

liberals and Black

power supporters. When the National Black Political Convention struggled to find a location Hatcher offered up Gary to host the landmark convention---even at the expense of angering the city's white population.

Ebony, People and The New York Times celebrated Hatcher's power moves. Gary's Post Tribune dogged his political steps For many white citizens, Hatcher symbolized racial divisiveness and political incompetence. In 1969, the Beaver County Times ("Secession in Gary") reported

that the city's Glen Park section proposed disannexation under grounds of racial preferential treatment and a

drop-off in city services. A city councilman lobbed a verbal bomb that was prophetic: "Gary's already dead. No one goes downtown anymore."

Adversaries accused him of pandering exclusively to Gary's African American citizens. Brushing off indictments of spending too much time away from mayoral duties, he made no apologies for his way of doing things:

"About one third of our total budget comes for the federal government. If I did not aggressively go after federal programs and grants and go to meetings with federal officials, we would not get those funds. So I never apologize to the people. The same people who criticize me when I leave the airport are the same ones standing there when I get back with the federal dollars, saying oh, boy, the mayor got some more money for us, some more jobs for us. I try to be straightforward with people. I tell them don't vote for me, if you don't expect me to go out of town because the only way I know how to help Gary is to do the things I do."

Opposition went beyond verbal. During his first term, Hatcher was shot at outside his home. A bomb was found in his trunk. Mysterious fires burnt out wiring in his cars. There were bomb threats and rumored assassination attempts.

Opinions formed across racial lines. In time, mounting frustrations knew no color even tho though a dark cloud of race, crime and politics had lingered over Gary for decades.

ACT III: BIRTH OF A NATION

| |||

| 1930 lynching in Marion, Indiana. |

Gary's rise coincided with Indiana becoming the center of Ku Klux Klan resurgence. A hundred miles south of the city---Klan activity spread across the state, infiltrating Indiana politics. Membership surged in Evansville and other towns situated around the state capitol. Non-profit organization The Equal Justice Initiative recorded 18 lynchings of Indiana African-Americans between 1880 and 1940.

Photographer Lawrence Beitler's 1930 image of Negro lynching victims surrounded by a mob in Marion, Indiana would become the most iconic photograph of lynching in America. That picture would go on to inspire the lyrics to the Billie Holiday's Strange Fruit (1937):

Southern trees bearing strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood on the roots

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees

Klan influence and Indiana's Protestant leanings and conservative views were in alignment with Middle America's views of groups considered a threat to America: Blacks, Catholics and Jews. Immigrant Poles, Hungarians, Serbians, Greeks and Slovak working in factories, plants and foundries littered across Detroit, Chicago, Western Pennsylvania and Northeastern Ohio were viewed with contempt and suspicion. Some native-born whites believed their European neighbors were clannish Communists out to steal their jobs and contaminate a post-World War I America with their socialist beliefs.

Generations before Donald Trump's birther/populist/anti-immigrant agenda, a clear distinction was established between theses two groups of the Caucasian persuasion. White native Protestants considered them "papalists" whose only loyalty was to the Catholic church. They were bohunks or hunkies---a reference to their Bohemian roots and sturdy physical appearance. (an alternative mispronunciation of these terms by Southern Negro arrivals lives on in 20th century American lexicon).

By the 1940s and 1950s, these immigrant groups forged a white ethnic working class that helped spur America's growth in manufacturing and production. Forming a a powerful voting bloc, shaped the political fabric of their cities. Their rocky road to assimilation is oft told and considered one of America's greatest success stories. Rarely discussed is another type of immigrant rite of passage---absorbing systemic racial attitudes directed at another group arrivals who didn't come through Ellis Island or arrive at port cities enroute to America's heartland. They arrived by car or train from Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas and Tennessee. Instead of European calamity, they fled racism and dismal conditions of the rural South.

Landing in Gary, African American were regulated to poor housing conditions and the worst jobs, they resided mainly around Gary's Midtown section---restricted from outer areas like Miller Beach and Glen Park unless they were laborers and "day workers"---African-American female domestics hired to clean homes of the city's affluent.

My mother was one of those women. She rode the bus to Miller Beach to care for children of a Jewish family named Kellman. She told me stories her female's employer paranoia of my seventeen-year old mother engaging in a sexual liaison with her spouse---another was rejecting a request that she wear the black-and-white maid's uniform signifying white "status" of being able to afford a Negro help. She refused to take the children on an outing to the neighborhood beach off limits to Black Gary citizens back in the '50s. Venturing there was the equivalent to signing one's own death sentence. My mother recalled that interactions with her Polish neighbors as cordial. Relations with Lithuanian ones were not so welcoming. Black workers cleaned stores along Gary's Downtown shopping drag but couldn't shop there. After dark, Broadway and Fifth morphed into a southern sundown town.

Transitional pathways enjoyed by their predecessors were closed to them. These racially-tainted systemic practices were masked by a rite-of-passage system writer Mike Royko branded as the bootstrap theory---an "onward and upward process" that was followed by

European ethnic groups that involved "putting in time in their rickety

neighborhoods and then moving on."

"Different strokes/for different folks"

---Everyday People (1969)

Besides poor housing conditions, Gary's Negro community were subjected to overcrowded schools. In response to emerging student integration in 1927, one student boycott that lasted five days. When 116 Black students were allowed to integrate a high school in 1945, 700 white students walked out, making media headlines. Singer Frank Sinatra showed up to attempt to stop the strike to no avail. The strike would last nearly two months. By '47 all Gary schools were integrated but the city remained segregated.

Keeping with the nature of American cities, urbanization and employment were always a source of

contention. During antebellum, the presence of free Blacks posed a threat to slavery's free labor system and Southern social order. As a result, free blacks struggled to make a living in areas where slavery thrived. Northern industrialists---preferring to maintain the social status quo---favored cheap immigrant labor and discouraged Black northern migration planting seeds of competitive dissension later.

Booker T. Washington seized an opportunity. Playing to the racial sensibilities of potential Northern philanthropists and benefactors opposing Black integration and migration to the cities, he secured funding to create Black "self-help" programs specializing in agriculture and technical vocational trades. Washington's strategy would advance Black occupational upward mobility via skill trades under the guise of maintaining post-slavery African-American labor pool needed in Southern rural areas.

"No race can prosper til it learns that there is much dignity

in tilling a field as it is in writing a poem"

---Booker T. Washington

Labor shortages and restricted immigrant US entry opened up Black migration to American cities to fill industrial labor voids. Deborah Rudacliffe's Roots of Steel: Boom and Bust In An American Steel Mill Town explore "race and class" politics pitting ethnic groups against each other in 20th century industrial America similar to conflicts between Gary's White, Black and Hispanic working-class. During this tense climate Gary avoided violent race riots that took place in neighboring East St. Louis and Chicago and faraway

towns like Omaha, Duluth, and Tulsa. Instead of mob violence, politics

and criminal activity would maintain the social order of things.

|

| 1919 lynching during Omaha race riots. |

|

| A postcard of a lynching in Duluth, Minnesota: 1920 |

ACT IV: SIN CITY

Like other Midwestern racketeering havens Kansas City and Chicago, Gary's reputation for gambling and prostitution earned the city a seedy reputation and distinct name: Sin City. During

the 1950s and 1960s, Gary's Lake County region was considered one of

the most corrupt counties in the nation. Lake County historian Bruce

Woods recalled the city's history of political tampering: "Gary had a

mixed population of many immigrants, perhaps making them susceptible

payoffs to voting. Precinct councilmen picked up Gary voters and drove

them to the polls and paid them to "vote the right ticket."

Turning a blind eye to shady

infractions from city government, Gary residents endured a succession of mayors and office

holders indicted for tax evasion and graft. Gangsters were forced

to contribute to campaign funds. Police officers were hired as enforcers

to deal with Gary business owners who voted "wrong." Court cases were

fixed. Prostitution houses were tipped off. The Chicago Daily News ("Dice, Cards, Girls----Reform Getting Nowhere in Gary") documented Gary's shady operations.

From his days as a city councilman, Hatcher opposed Gary's climate graft and corruption. Moving quickly to dismantle ways of the political old guard, he scrapped the old patronage system that parceled out city jobs to political cronies and supporters. Instituting a merit system opening up civil service opportunities to all, Hatcher professed that "victory presents an exciting challenge" and professed that urban cities in America need not "wallow in decay." Pledging himself to the cause of "reviving" the people and "rejuvenating" Gary, he aspired to prove that "diversity could be a "source of enrichment" as proof that people in at least one American city could---in the hip sixties slang of the time--"get themselves together."

While expressing his intent to be "mayor of all people," Hatcher didn't disguise the fact that Indiana's Black population had "been suffering and getting the short end of the stick in every area of life." Reports from the Indiana States Civil Rights Council revealed that only 28 percent of Black Indiana residents held city jobs. Gary was ranked 34th in all 42 Indiana cities where Blacks were municipally employed.

Hatcher broke from Gary mayoral tradition in many ways. He held regular press conferences. Pushing back against the city's longs-standing agreements with industrial giant US Steel who employed 65 per cent of the city's population--Hatcher challenged inequitable tax structures and proposed that corporate property taxes and revenue be funneled back into the city to improve schools and housing. He convinced US Steel to modify employment policies to underemployed and under-educated into the workforce as well as provide financial incentives tied to their education completion. Th e renewed pact resulted in the donation of 145 acres of land for parks, a boat marina and construction of 500 low-income homes.

Local insurance companies and banks were tapped to provide business and mortgage loans to Gary's undeserved residents. Plans were on the table to revitalize the neglected Midtown neighborhood and expand the city's airport. In the tradition of legendary urban planners like Robert Moses---the man who behind the construction of New York City's parkways, bridges and tunnels and parks---Hatcher's visionary accomplishments are unsung.

These mayoral platforms echoed DC Mayor Marion Barry's inner-city summer job programs and his avocation of government jobs becoming open to Black constituents that would propel them to middle-class status. They mirrored Maynard Jackson's inclusion policies in business and the boardroom when corporate organizations came calling to put down roots in Atlanta.

ACT V: THE END OF GARY'S GLORY DAYS

According to the Post Tribune, Gary's population peaked at 175,000 by 1970. 32,000 steelworkers employed by US Steel. Seven high schools were at full enrollment. Native sons and daughters emerged from the city and surrounding areas to make their mark in politics, sports and entertainment----including five brothers from Midtown who were America's biggest recording act that year. As New York teetered toward bankruptcy and cities like Detroit and Newark struggled to recover from social unrest ,Gary seemed like an oasis. The city's working class toiled in the mills and factories all week. On weekends, they tended to modest bungalows and single family homes and tinkered with their GM chariots---all paid for by steady salaries and overtime pay.

Good times wouldn't last. Shifts toward international trade and foreign steel production caused Gary's mill jobs to dwindle down to 6,000 by the end of the decade. A decade of white flight drained the city's population to around 100,000. Since early '71, Northwest Indiana's outer outer suburbs were exodus destinations. Some businesses willingly pulled up roots. Others made the move due to fear of rising insurance costs if they remained. Overnight, rural areas became self-sustaining communities collectively known as "the region."

For all of Hatcher's reform efforts, crime plagued his administration for years. A violent drug war between factions of heroin dealers looking to control the city's drug was captured in a 1972 Time Magazine article ("The Nation: The Godfather in Gary"). Chicago gang activity infiltrated the city. During the summer of '84-- three years after the Atlanta Child Murders---a violent Midwest murder spree threw the city in a panic. A year later, four teenagers were sent to prison for the murder of a senior citizen. That same year an owner of two popular family restaurants was killed in front of one his businesses.

The Miracle City was on its way to becoming the nation's murder capital. In '87 Hatcher's mayoral run came to end.

Weary of Hatcher's devotion to national affairs instead of focusing on the "nuts and bolts" of municipal management. Gary never returned to its lofty perch as Indiana's major economic hub. County and state politics had blocked Hatcher's later growth initiatives. Towns like Fort Wayne overtook Gary in commerce and population. Indianapolis---long a benefactor of Gary's tax revenue in the past---grew from a sleepy state capital to a Midwestern metropolis.

A revolving door of mayors came and went. Stagnant leadership, fiscal mismanagement and bungled opportunities defined their administrations contrasting to the succession of municipal leaders who were major catalyst of Atlanta's growth over the past five decades.

Gary's failure to reinvent itself as a multi-industry sector city they way ex-Rust Belt areas like Pittsburgh would was also attributed to Indiana's hands-off approach toward rebuilding. In 2019, Indiana built up a revenue surplus of S410M. Proposed infrastructural projects were scrapped. None of these projects included Northwest Indiana.

For three decades, Hatcher and Gary's decline have been eternally linked. It's now time to reassess his legacy with a more clearer focus:

1. Hatcher was guilty of Black cronyism. False. Isolated by Gary's Democrats and Republicans machine opposing his run for office, Hatcher secured a trusted circle of cabinet members when others declined to work with him after his victory.

2. Gary's white flight/tax base decline was instigated by race. Partially. African American outward response to Hatcher's mayoral nomination, and opposing views of his efforts to dismantle Gary's systemic treatment of its Black citizens, integration and rising crime triggered an exodus of white residents to the suburbs although many remained behind.

Jerry Davich's book Crooked Politics in Northwest Indiana, also reveals Hatcher's reformed-minded policies also prompted Gary's corrupt former city officials and political opponents to leave the city and orchestrate the departure of the city's valued tax base.

3. Hatcher's incompetency ruined the city. False. Gary's prosperity and growth was contingent on two factors---a healthy manufacturing industry and then-current federal government commitment to urbanization: The departure of presidential ally Jimmy Carter and the arrival of adversary Ronald Reagan saw a shift toward smaller government and reallocation of federal dollars. Industry decline during a nationwide recession was the nail in the coffin.

4. Crime was Hatcher's Achilles heel: Yes. During Hatcher's final years in office, Gary landed in the top 10 of cities with populations over 100,000 with high murder rates---averaging just over 30 homicides between 1986-1987. Municipal wrong-doings and organized criminal activities existed before Hatcher's arrival but rising violent crimes would define his future legacy.

ACT VI: LEGACY RESTORED

In 2020, Gary is in a holding pattern. Languishing in an uncertain limbo----hanging by a thread of civic pride. Near and far, current and ex-citizens maintain a firm hometown attachment that defies distance. Without anchoring basic amenities or a stable business infrastructure to attract investors, redevelopment prospects for Gary are daunting. To offset fiscal challenges, the city's golf course and convention center have been put up for sale.

As the city remains at the mercy of Indiana's opposing politics and tight-fisted fiscal policies, Hatcher's bold audacity, presidential relationships and wide-ranging influence are very much needed. One can only wonder what Gary's future would have been like in another time and under different circumstances.

One can imagine if Hatcher was able to use his scope of influence to lure other industries to Gary the way CNN and Delta Airlines set up shop in Atlanta or having access of decades of presidential financial aid the way Mayor Fiorella La Guardia did to build airports, bridges, parks and highways that would modernized New York City.

Decades after its Rust Belt decline, Pittsburgh climbed out of economic decline, reinventing itself as a prosperous city through its higher-learning facilities, industry diversification and a reinvigorated population.

- We

can only wonder what Gary's future would have been if Hatcher used his

international platform to embrace Central American, Latin American and

African immigration---diverse energy that economically transformed

cities like Dallas,

Houston and Minneapolis. What would have happened if he followed Pittsburgh's

- Maybe he would have leveraged Gary's prime location as a transportation hub and further expanded into rail and air.

- What if Hatcher had taken Carter's advisor on urban affairs in 1977? Would he have been able to transform Gary's fortunes from within? What if he held the position of secretary of housing and urban development instead of the incompetent Ben Carson?

It's time to overturn the guilty verdict dooming Hatcher's legacy. It's easy to lead a city under prosperous conditions. It's another thing to lead it under less than favorable ones. Running a city lodged between the third-most populous city in America and thriving towns with their tax-bases is not for the faint of heart or less-gifted leader.

As Gary struggled in the later years of his administration---outsiders attempted to seize control of the city's remaining assets like its airport.Recognizing the Gary's potential as a transportation hub, he refused to relinquish control. Under Hatcher's watch Gary took tenative steps toward becoming the Atlanta we see today---from hosting the '72 National Black Convention to forging relationships with Black entertainment race men like Bill Cosby, Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier who turned up at local political fund raisers to offer their support---similar power moves continue to bear fruit for Atlanta's lucrative entertainment-commerce-entertainment trifecta today.

The next time you hear a negative comment or barbed crticism about Richard Hatcher, understand what he gave up---a coveted govermment position that could have furthered his political career. A possible presidential run. Lucrative book deals and speaking engagements. As Gary's fortunes rose and fell, Hatcher refused to abandon ship. A succession of Gary mayors during the post-Hatcher years have seized the mantle but none have come close of duplicating his visionary accomplishments.

Hatcher's predecessors held court under a brighter climate of economic stability masquerading as Gary's glory days that we all wish for but make no mistake----there's nothing easy about being the first. Hatcher symbolized the biblical reference stranger in a strange land--He was racially out of step with the status quo. Intelligent, worldly and educated---he played the entire political chessboard instead of remaining in the comfort zone of regional politics. A sophisticated leader of a blue collar city of immigrants and southern transplants--- maybe too sophisticated ---he may have been better suited for the larger political stage he rejected.

Hatcher was a rare breed. He operated with no blueprint outlining how to be a man both of his time and ahead of it.

For all of his vision and urban renewal expertise---he was unable to look far enough in the future to predict Gary's single-industry collapse----and move quickly to install economic anchors to diversify the city's fortunes. In moving forward---he could have outlined a plan to linked Gary's blue collar past with its new future---much like ATL's civil rights legacy was major part of its cosmopolitan makeover.

Shortcomings aside, his gifts are unmatched to this day. Maybe the political roadmap he charted would be a perfect compass for Gary's current crop of policy makers to utilize as they attempt to navigate Gary through turbulent waters enroute to a more favorable destination.

Comments

Post a Comment