The Budweiser Superfest and the Business of Black Music by Sheldon Taylor: Part 2: The Show Must Go On

Budweiser Super Fest lineups were a throwback to music package tours emerged during the 1950s and 1960s. Void of seamless logistics that made the Super Fest run like clockwork, they were bare bones affairs. In 2021, Boyz II Men's Vegas residency moves into its eighth year, a far cry from yester-year's circus arenas, civic auditoriums and hole-in-the wall venues.

1971's live rendition of Sex Machine and '72's Mind Power, finds Soul Brother #1 James Brown name-checking cities along the chitlin circuit: Richmond. Philly. Harlem. Baltimore. Chicago. Detroit. Theaters dotted their main streets with names luminous like planets in the sprinkled across the galaxy: Hippodrome. Uptown. Royal. Apollo. Regal. Fox.

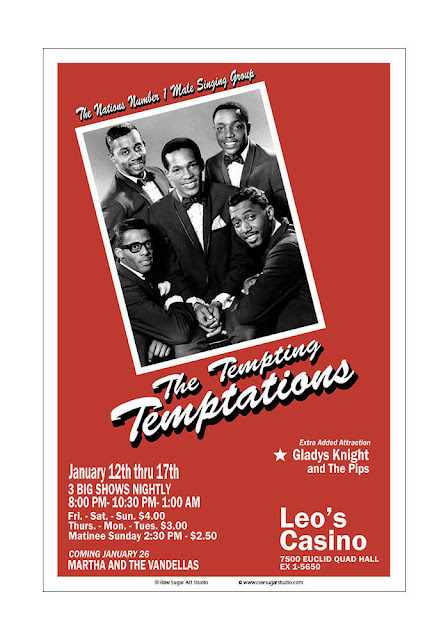

Rudy Guarino's Sugar Shack in Boston, Leo's Casino in East Cleveland and the Latin Casino were stops along the Black tour circuit were a step up. Hot acts played a couple shows night. Up-and-comers played more. Seating 700-1000, these clubs were alternatives for entertainers who'd never play the New York's Copacabana crowd like Sam Cooke.

Motown elite the Miracles, the Supremes and the Temptations were heavily booked in spots like Leo's. These nightclubs would provide a valuable training ground for the groups to hone their stage craft before they followed Cooke's footsteps and made the jump to the Copa.

There was the Total Experience in South Central Los Angeles. The Club Harlem in

Atlantic City. Phelps Cocktail Lounge in Detroit. Perv's House and the High Chaparral on Chicago's South Side. These clubs thrived back in the days when entertainers plied their trade in blue collar fashion. Lines were blurred between the common folk, street people and celebrities who mingled freely. The real superstars though were the underground crowd who were"in the life."

The hustlers and the dealers made

life easy for nomadic performers---the kind depicted in soul troubadour Bobby Womack's soul soliloquy Facts of Life/ He'll Be There When The Sun Goes Down. Entertainers were be given safe

passage when they arrived in cities. They were steered toward the best drugs and beautiful women.

When 1972 film Super Fly was filmed in New York City, Local pimp "KC" donated money, his wardrobe and even allowed his customized Cadillac to be used in the film.The Ward brothers provided protection for film crews during filming of 1973's The Mack shot in the streets of Oakland, home base for R&B vocal group the Whispers----favorites of the pimp crowd.

Some places were less welcoming. In memoir Truly Blessed, Teddy Pendergrass recalls "incurring the wrath" of

jealous pimps fearful of losing their women to traveling entertainers who they

considered "less than nothing." When sinister gestures of an audience member became a bit too much, TP canceled a late Apollo show and returning his 100k fee.

Performing in these venues could also be dangerous. During a 1972 late night Easter show at the Club Harlem featuring singer Billy Paul, a shootout erupted over a Philly black underworld drug dispute. Among a packed crowd of over 500, eleven were wounded and two died in the melee. Off stage, it was also hectic. When Al Green ventured into a barbershop in a seedy part of Cleveland during a break from touring, he was assaulted and robbed of his jewelry./

"I got me a plane. But the difference with me, I'm gonna take my whole band and save some money. I got a big enough plane to take everybody, ain't gonna be like (James) Brown flyin' on a plane while my band is on a riggidty bus. It ain't right."

---Otis Redding (1967)

It wasn't uncommon for entertainers to log 100,000 miles a year on the road, Weary of the grueling conditions, Otis Redding purchased a $78,000 twin-engine Beechcraft to fly to gigs. Months later after playing a show at Leo's Casino, his plane plunged into an icy Wisconsin lake just minutes away from his destination, killing all aboard except a single passenger.

In 1970, soul singer Billy Stewart and two members of his band suffered a similar fate. They drowned in a North Carolina river after he lost control of his new Thunderbird that malfunctioned as he crossed a bridge. Three years later and less than 200 miles from Stewart's fatal location, Stevie Wonder nearly succumbed to head injuries sustained in a car accident.

Navigating the south was especially treacherous. In You Send Me: The Life and Times of Sam Cooke, writer Daniel Wolff revealed 1950s Black music's popularity, its gradual movement beyond racial "restrictive covenants" and the occupational hazards Black entertainers faced while touring below the Mason-Dixon line.

In Birmingham, Alabama crooner Nat King Cole was beaten by mob while onstage. R&B singer Jesse Belvin's car tire were slashed while on tour in Hope, Arkansas. He died in a head-on collision en route to his next performance. The Five Heartbeats's chilling scene finding the group at the mercy of racist police crooning for their lives is a menacing metaphor for similar encounters R&B acts of the fifties and sixties endured on the road.

"You must separate yourself from your job": Jackie Wilson

Jackie Wilson probably endured the worst of any entertainer of the era. Tethered to the mob his entire career, he suffered in perpetual servitude. Hung out of penthouse windows and locked up in rat-infested basements by his handlers---Wilson never broke free of the strong-arm tactics binding him to contractual peonage for nearly two decades.

Arriving to venues in slick suits and fly cars, Wilson's cocky persona was a threat to the Jim Crow south's status quo. His stage charisma resonated with white female audiences. Enraged local law enforcement moved to put Wilson "in his place." In Louisiana, police broke his ribs. In Texas he was stomped by police officers. After these encounters he was forced onstage.

Wilson's brother-in-law and traveling companion witnessed it all and shared the experiences in Tony Douglas' Jackie Wilson: The Music, The Man and The Mob:

"He took shit from everybody and survived it over and over again. He got beat up and came up singing. He got whipped and came up singing. He got sued and came up singing. He was true to his profession. I watched them beat his ass and they told him "You have to go out there. If you don't, I'll kill you." They had me in handcuffs and kicked my face in. He sang like an angel...bloody as hell....cracked notes...clear as bell. He said to me---you must separate yourself from your job....

I watched him sing with cracked ribs, a cracked jaw with a gun to the back of his head. Do you know what it was like for a white man to find out his daughter, wife and sister were in total awe of a black man in the south? They were still lynching then. You have to sing to these bitches.

The Klan would take care of them. "I don't care what you do--make sure he walks out and shows those niggers (in the segregated area) upstairs....I don't care what else he does---he does the full show. He had to walk out on stage with blood on his shirt---he announced to the audiences "I want to thank the audiences who kissed tonight".

Collins lamented Wilson's treatment on the road:"Nobody cried for him when they beat him almost to the point of death and he went out on stage and sang that night. He went down right downstairs where the paramedics were waiting and they took him to the hospital, 'cause he was bleeding internally. The Texans said, "Well the nigger deserved it."

In Soul Survivor: A Biography of Al Green, band members recall how Green begged off a show during a scheduled series of theater-in-the round gigs in Florida ("I don't feel good. I don't feel like singin' tonight"). When he got "chesty" with theater owners, a goon showed up to his dressing room. Ten minutes later another individual arrived carrying a satchel.

Green did the show---with a broken arm set in a cast. He would later turn up on Soul Train, delivering a magnetic performance with his arm in a sling. According to Green's bodyguard after the Florida incident "was when Al started carryin' a weapon."

Up Next: Money and the Power & The Teddy Bear and the War of Gods.

Comments

Post a Comment