STILL NEVER TOO MUCH: BASKING IN LUTHER'S GLOW OF LOVE BY SHELDON TAYLOR

"Everybody can't jump on Prince's thing. People need romance. It's like a pendulum swing. After the bam-bam-bam, the love songs will always be there.”

Prolific songwriter Linda Creed's 1985 declaration in Billboard wasn't a jab at Prince's sexual shock-and-awe or an attempt to rain on his purple parade. It was a well-refined modus operandi.

During the 70s Creed penned many of the Philly Soul songbook's most durable hits. Two of them ("You Make Me Feel Brand New" and "People Make The World Go Around") would spawn over 100 remakes across multiple music categories. Before she was thirty, Creed earned over 20 gold and platinum records and a half-million dollars in royalties.

SEE: THE GREATEST LOVE OF ALL: A STORY OF CANCER, COURAGE AND COLLABORATION

Now the jewel of her catalog was primed for a makeover. 1977's "The Greatest Love of All" would be revived for Whitney Houston's debut album. A year later, Creed lapsed into a coma as Love climbed the charts. She'd be dead by the time Love hit the #1 spot.

Creed's posthumous success was a fitting epitaph: After the bam-bam-bam, the love songs will always be there.

Step into the lush champagne-and-roses world of the shoulder-pad-clad 80s love man: He's thirtyish. His hair is sculpted in a perfectly trimmed natural or sleek texturized style. Impeccably dressed in tailored suits or loose-fitting Italian ensembles, plush suede or buttery leather loafers adorn his feet. A Vuitton clutch bag is nestled under his arm.

Cool as a brisk spring day---he's smooth as Harvey's Bristol Creme or Chivas Regal.

His audience? A 25-45 adult demographic partial to

a plush kind of R&B writer Virginia Prescott described as "refined to

a patina" and "shiny as a new Mercedes."

Think Teddy Pendergrass’s raspy romance. Alexander

O'Neal's 808 and heartbreak. Howard Hewett's silky smoothness. Peabo Bryson's

soaring balladry. Jeffrey Osborne and

Glenn Jones' earnest baritone/tenor voices smolder with intensity. Freddie

Jackson's string of number one hits turn up the heat.

Enter Luther Vandross.

Writer Naima Cochrane crowned him “the definitive quiet storm voice.”

While others seduced or serenaded, Vandross curated. With the keen eye of an antique dealer, he plucked songs from yesteryear ("Superstar" "Creepin'" "If This World Were Mine") and refashioned them into Quiet Storm classics.

Cochrane encapsulated his greatness in Vibe:

"He (Vandross) doesn’t have the depth and urgency of church-bred vocalists, but instead he has the virtuosity of an opera singer – Luther would stretch his songs out, and walk through them slowly, unhurriedly, switching the arrangements up two or three times in one song but never losing control of the vocal"

Craig Seymour’s brilliantly researched The Life and Longing of Luther Vandross likened the singer's peppy jams ("Bad Boy/ Having A Party," "I’ve Been Working") to the “chaste good-time feel of Motown-era songs." The creamy-voiced singer's ballads ("If It’s Really Love") were described as aspirationally "slick and luxuriant.”

Black female singers were Vandross's ultimate muses but he also tapped into the spirit of legendary male vocalists from Black music's illustrious past.

Leaping from Billy Stewart's stutter-step scat ("Never Too Much") to Sam Cooke's gift for observation ("The Other Side of the World") in a single bound, he also shared Al Green's penchant for the covers ("How Can You Heal A Broken Heart"). While Green wandered where the feeling would take him, Vandross held the romantic reigns steady.

The scent of Smokey's lyrical whim lingered over 1982's "Promise Me":

"I can only speak for the things that I've been through

but when it comes to our love

I'll talk the whole night through"

Offering listeners a panoramic view outside his wistful window, Vandross transported them to a world where true love was elusive and fleeting.

Sometimes it was within his sights. More often than not---it was just beyond his grasp.

'83's "Make Me A Believer" finds Vandross in a rare moment of pursuit ("let's be lovers"). Subtly moving from seducer to seduced ("I know the way to persuade me to your side/and I am sure you can."), his optimism is infectious:

"Superman can fly high up in the sky

cause we believe he can

but what we choose to believe will only come out right"

Vandross's sensitivity is his golden parachute. It offers a safe landing into the arms of anyone who ever had the heart to reciprocate his love. It softens the impact of emotional heartbreak. Triggered by romance's rip-cord it opens to "You're The Sweetest One's" angst-ridden monologue ripped from the pages of a confectionary teen dream:

"Dear diary, I know I've said this before. But I'm sure this time. It's really love."

Beneath Vandross's smooth veneer beat a heart quickened by the push-and-pull of love's ebb and flow. No one mastered mood and melancholy better:

''There's a chance for me and you and I

I surely feel like the time is near the picture is in my mind is clear

that love has brought us here”.

“Wait For Love"(1986)

"Sad but I thought that maybe/love wasn't meant for me"

“The Other Side of The World" (1985)

In liner notes penned for 1996's greatest hits package The Freddie Jackson Story: For Old Times Sake, Prescott praised the sentimental soul music Vandross sang about: "admitting vulnerability doesn't mean impotence. Vulnerability is a turn-on."

In Vandross's era, R&B albums tended to be work-for-hire affairs parceled out to a hodge-podge of producers. Phyllis Hyman's Living All Alone and Whitney Houston's debut aside---many lacked the sonic and singular identity of Quiet Storm masterworks like Freddie Jackson's Just Like The First Time or Anita Baker's Rapture.

Vandross's consistency was grounded in his belief that strength was in numbers.

His session players doubled as his touring band. Arranger Nat Adderly, Jr. brought majesty and elegance ("Forever For Always For Love"). Songwriting partner/bassist Marcus Miller's spry bounce ("Give Me The Reason", "I'll Let You Slide") and subtle bottom ("Anyone Who Ever Had A Heart") were cornerstones of the Vandross catalog.

Background vocals were a Vandross signature. Fonzi Thronton, Lisa Fischer, Kevin Owens, Ava Cherry, and Robin Clark rounded out a cadre of stellar vocalists prominently featured on albums and live shows. "Wait For Love'" featured their breathless pitch-perfect hook recalling Vandross's beloved Supremes' "Stop (In The Name of Love)." They added sassiness to the finger-waving "It's Over Now." Their party-hearty vibe on "Bad Boy/ Having Party" hints at the festive intro to Marvin Gaye's "What's Goin' On."

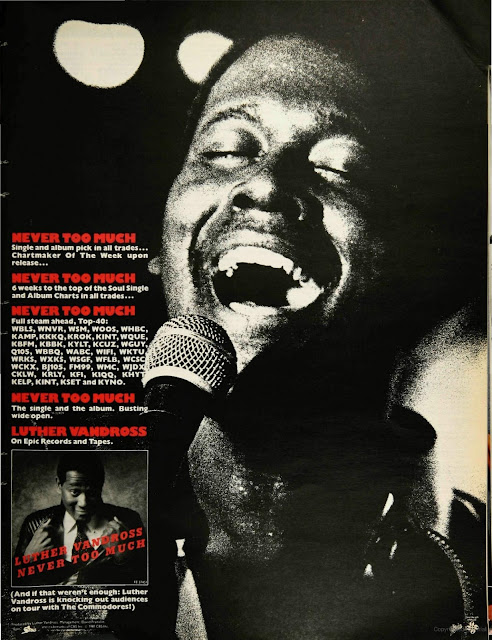

Record buyers responded. Vandross's first seven releases---Never Too Much (1981), Forever For Always, For Love (1982), Busy Body (1983), The Night I Fell In Love (1985), Give Me The Reason (1986), Any Love (1988) and Power of Love (1991) all went #1. Every album would enjoy platinum or double platinum sales.

As new releases ran up the charts, older material continued to move hundreds of thousands of units. In early '85, Vandross scored two platinum albums in a single year. 1989's greatest hits package The Best of Luther Vandross, The Best of Love sold steadily for a nearly a decade moving three million copies by 1997.

Subsequent releases Songs, Never Let Me Go, Your Secret Love would sell a million copies or better. It wasn't until 1998’s gold-selling I Know---praised by Billboard “as a testament of what a real love song should be rather than the bump-and-grind workouts that tend to masquerade as 90s romantic music” that Vandross’s 17-year platinum streak. was broken. He'd return to form with 2001’s platinum Luther Vandross.

Throughout the 1980s, Vandross was everywhere. He was an in-demand producer, orchestrating career comebacks for Aretha Franklin, Teddy Pendergrass, and Cheryl Lynn. His albums were strong sellers. Tours were regular sell-outs. Well respected by his industry peers he appeared on their albums.

Stevie Wonder's "Part-Time Lover" echoed the breezy bounce of Vandross's uptempos and raced to the #1 spot on the pop, R&B, and dance charts thanks to the Vandross's signature scat that anchored the record.

Despite these successes, public acclaim and opportunities enjoyed by others eluded Vandross. He flew under the radar of Michael Jackson and Prince. Anita Baker and Whitney Houston enjoyed Grammy wins, heavy crossover airplay, and video rotation. James Ingram, Peabo Bryson, and Lionel Richie were pop/adult contemporary fixtures.

In '83 Patti Labelle was an R&B veteran with a gold album with two major hits ("Love Need and Want You", "If Only You Knew"). A year later she ascended to pop star singing perky songs ("New Attitude," "Stir It Up") that hinted at Vandross's upbeat style.

Vandross watched the parade go by.

During a press run promoting '98's "I Know," he placed the blame at the feet of his record label:

“There was always a tug of war (at Epic). They never wanted me to produce myself. They didn’t like much of what I did. It was just hard to hand over (my project) to another producer because I felt I was qualified…..I have no problem with other music that is given to me but I’d like to be able to work with my music first.”.

Seymour's work examined these omissions ("why isn't Luther Vandross a household name?"), peeling back the layers of Vandross's frustration:

“I want a number-one (single) like Lionel Richie and Natalie Cole and Whitney Houston and all my friends who come to my house, I don’t think that is unreasonable. I think my record company should know that is something I aspire to….the missing link is the performance of the company to get that for me.”

Nevertheless, pop's greatest omission was one of R&B's greatest heirlooms.

Audiences heard Vandross before they ever saw him. His vibrant voice was a fixture on TV/radio jingles circuit. His sparkling backgrounds graced David Bowie's "Young Americans" (1975), Chic's "Everybody Dance" (1977) and "Le' Freak" (1978), Quincy Jones' "Songs...And Stuff Like That"(1978) and Sister Sledge's "We Are Family."

Anticipation grew after Vandross's lead vocals on R&B/dance band Change's "The Glow of Love and Searching." The response to these stellar performances nudged Vandross closer to the spotlight, destined to pull him out of anonymity's shadows for good.

I can remember the first time I heard Vandross. I was 11 years old. It was 1980. A year earlier I’d upgraded from kiddie records to buying Shalamar ("The Second Time Around") The Gap Band ("Oops"), Michael Jackson ("Working Day and Night") Prince ("I Wanna Be Your Lover"), and Kool and the Gang ("Ladies Night") 45s.

Since albums were out of my fiscal reach, I turned to late-night radio to get an aural clutch of what I could not touch: "Rapper's Delight", "Freedom" "Christmas Rappin'" ("The Breaks" was a couple months away) Jocko's "Rhythm Talk" crept into radio playlists alongside hot records like McFadden and Whitehead's "Ain't No Stoppin Us Now," and Chic's "Good Times."

One particular night a jaunty voice came through from my tinny clock radio speakers, spinning a tale akin to songwriter Rod Temperton's fly-on-the-wall nocturnal narratives crafted for Heatwave ("Boogie Nights, The Groove Line"), Michael Jackson ("Off The Wall") George Benson ("Give Me The Night"), and The Brothers Johnson ("Stomp!"):

“Hit the town in the cold of the night

lookin’ round for the warmth of a light

there was fog on the road

so I guess no one saw me arriving

I was tired and awake for some time

Then my lights hit a welcoming sign

It said if you're alone

You can make this your home

If you want to….

"Searching's" ominous synth riff sets the mood. Vandross emerges from the foggy darkness, landing at the doorstep of a hedonistic nightclub. Hypnotic strobe lights flicker seductively. A "girl in love's disguise" appears and makes her play ("what I've got's/ hot stuff/the night is ours"). Vandross rebuffs her sexual advances ("I just wanted to dance") and retreats in a hazy shady of regret ("what was I doing there/far away from nowhere?")

Somewhere, I'm sure Michael Jackson ("Heartbreak Hotel," "Thriller") was listening.

Future songs like "The Night I Fell In Love" would showcase Vandross's gift for imagery:

"The stars were shining

brighter than most of the time

than love came out of nowhere

no thrill would ever beat

the night I fell in love"

Vandross's arrival was perfect timing.

Had his career

begun a decade later, he might have suffered the fate of Jocelyn Brown

and Martha Wash, the faceless voices behind massive 90s dance hits ("Gonna Make You Sweat (Everybody Dance Now) "The Power", "Everybody, Everybody") who weren't given credit for their contributions.

Maybe Vandross would have been a historical footnote---a gifted and talented cadaver exhumed for the 2013's brilliant Twenty Feet From Stardom film detailing the career highs and lows of background singers in the music industry.

Early pursuits of a solo career fell flat. In the era of Teddy Pendergrass's virile swagger and Peabo Bryson's white-suited cool---record labels passed on the rotund and dark-skinned singer with the golden voice. For a time, Vandross retreated back to his safe and (lucrative) cocoon as an in-demand sessions/jingles man and backup singer.

Re-emerging with a self-financed project that was the genesis of his debut Never Too Much---Vandross had a new agenda: he would take control of his career. After years of playing backup for a galaxy of stars, Vandross would become the self-contained master of his own universe: a full-fledged artist, producer, entertainer, and businessman:

"It was non-negotiable. The labels wouldn't accept me as my own producer. I got turned down by a lot of labels so I just thought I'd wait it out. I was making plenty of money as a jingles singer; it wasn;t like I was in financial need. I held out because I thought I was good---at least as good as the records I was hearing.

LL Cool J, Mariah Carey, Jay-Z, and Mary J. Blige's staying power is oft-celebrated. Vandross' quiet durability and dominance are lost to history. Outside of the realm of Black culture, he's a relative unknown blasphemously dismissed by New Music Express writer Rob Fitzpatrick as an "eighties cornball"

When ongoing configurations of contemporary Black music swept away careers like cyclone, Vandross survived and thrived throughout post-disco, funk, and dance-oriented R&B, rap, new jack swing, and hip-hop/soul eras.

As of 2021, Vandross's 1997 One Night With You: The Best of Love and 20006's The Ultimate Luther Vandross compilations have gone platnium. Debut single "Never Too Much" has sold a million digital downloads, forty years after its release.

Vandross's catalog was sample fodder for years. 1981's percolating "Don't You Know That" turned up on Heavy D's "Got Me Waiting." EMPD lampooned Vandross's "So Amazing" for "So Watcha Sayin." Pharell lifted 2001's "Take You Out's" hook for Jay-Z's 2006 "Excuse Me, Miss." In 2004, 1982's "Better Love" turned up on Young Gunz' "Betta Love" and Carl Thomas's "Make It Alright" remix. Janet Jackson's "All For You" sampled "The Glow of Love." The evergreen "A House Is Not A Home" showed up on Twista's "Slow Jamz" catapualting Jamie Foxx and Kanye to music immortality.

Robin Thicke and Justin Timberlake's modern blue-eyed soul penentrated the upper reaches of urban music drawing on Marvin Gaye's multi-tracked moody blues and Michael Jackson's percussive tenor for inspiration. No one has been has been able to completely crack the code to Vandross pageantry and pedigree.

There have been moments.

Ne-Yo's nimble theatrics and smooth tenor recall MJ's elastic influence but a closer look behind the lens of "So Sick" and "Do You" and you'll find Vandross's eye for lyrical detail. 90s balladeer Keith Washington modeled Vandross's genteel balladry ("Make Time For Love"). Self-proclaimed Emperor of Soul Will Downing's string of exquisite remakes stretches three decades and counting.

Carl Thomas has Vandross's pensive vulnerability but it's Jaheim who comes closest in capturing his essence. Whether painted in broad strokes or accented with slight flourishes, the gruff-n-ready singer's music are like ice cubes in a single-malt scotch, unleashing an intoxicating aroma of Vandross's illustrious past.

"Love Is Still Here/Forever" recreates Vandross's delivery right down to "A House Is Not A Home's" shimmery curtain-closing finale. "In My Hands's." models "Because It's Really Love" and "The Other Side of The World's" pristine production and recaptures "Make Me A Believer's" enchantment:

"I woke up on the top of the world today

holdin' her hand, she don't mind me leadin' the way

as long as I don't let her fall, she wouldn't have to pull away

gypsy woman can you read my palm, is my lifeline broke or is it long?"

Like fellow sentimental soul Linda Creed (“The Greatest Love of All”) ---Vandross would craft his own "career song" (“Dance With My Father”) that finally gave him the industry acclaim he sought. And like Creed, health challenges lurked behind the music, ultimately snatching away his momentum they way a horrific car crash would alter the life of Pendergrass—-the singer he'd supplant as R&B's #1 love man.

Luther Vandross's legacy is like a moving target. Hard to pin down. He's a soothing remedy to funk and disco and Michael and Prince's contact high. He's Dionne Wawick's urbane precision and Donny Hathaway's vocal mastery revisited. He's Motown's quick-paced folkiness and Brill Building hit factory all in one----a star of a musical motion picture inspiring multiple viewings that are never too much.

God emcee Rakim’s lyrics from 1992’s “Don’t Sweat The Technique” sum up Vandross’s timeless body of work he left behind:

“Poem's physique never weak or obsolete, they never grow old, techniques become antiques.”

Comments

Post a Comment